What I Do, And How I Do It

Not wanting to abandon the drip technique, I took a 180 degree turn from Jackson and started creating highly representational poured paintings. As I focused on large-scale portraiture, I fell into what might be called a Chuck Close/Jackson Pollock fusion. With all my paintings, the paint is either poured or thrown to create the image. Brushes are used only for the large color fields (usually backgrounds or to correct grievous errors), although I do sometimes manipulate the paint once it has landed on the canvas, using either a stick or a rag. The canvases typically receive the paint un-stretched, on the floor. Later they are stretched and final touches are added.

Most recently, however, I’ve been pouring my paint on already-stretched canvases inscribed with a charcoal grid. This grid idea is very much a nod to Chuck Close, so it is no accident that the first grid painting I completed is a portrait of him entitled “Close, But Not Quite.” The grid in this painting is readily apparent (Scroll down two posts to see this painting).

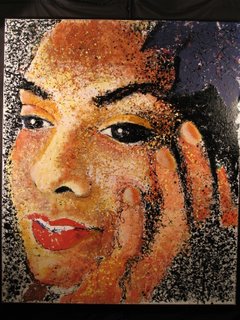

In “Michelle A.”—another grid painting, shown above—it is less noticeable, but traces can be found on her cheek and chin. In each case I lay down the paint on a given square while the adjacent surface of the painting is masked from view. This creates a disconnect, square to square, that I think adds to the controlled chaos, the vitality of the image. This disconnect can be easily seen in the rims of Close’s glasses, for example. Then at some point I begin dealing with the canvas as a whole, bringing the squares together, to a greater or lesser degree, and resolving the image.

When people ask me what I like about my paintings, I usually mention how the works react to changing light conditions. Well lit, a typical painting of mine glistens as the high-gloss whites and yellows catch the light. At dusk, the whites recede and the surface takes on a softer, richer glow as the earth tones expand. In a dark room they are positively otherworldly. I also like that the technique more than justifies the paintings’ scale (typically six feet by five feet). It, in fact, demands such size to accommodate the imprecision of the gestures. But most of all I like how such a crude method of painting can yield such a sensitive product. Look closely and you will see how filigrees of silver, white and yellow meld with rich reds, blues, greens and browns, combine with debris from the studio, a little cabernet sauvignon or a clementine pit, sometimes some bourbon, tossed or spilt, and build, layer upon layer, to finally resolve into a compelling whole.

Re-jiggering the calculus of the drip technique has created what I believe is a unique and recognizable portrait style for me. But beyond that, it allows me to walk in the shoes of painters I admire very much; to investigate Close, Vermeer, Duchamp, Pollock up close, but remain, at the same time, my own man. I am currently working on a painting entitled “White Rothko” which is a monochromatic, dripped interpretation of his signature works that has as much to say about Jasper Johns as it does about Mark Rothko. This is a great privilege and good fun at the same time. Titian beckons, but I’m not sure I have the energy.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home